The Story of St James as told in the Wall Paintings at Stoke Orchard: (Download the full PDF file here).

The Wall paintings

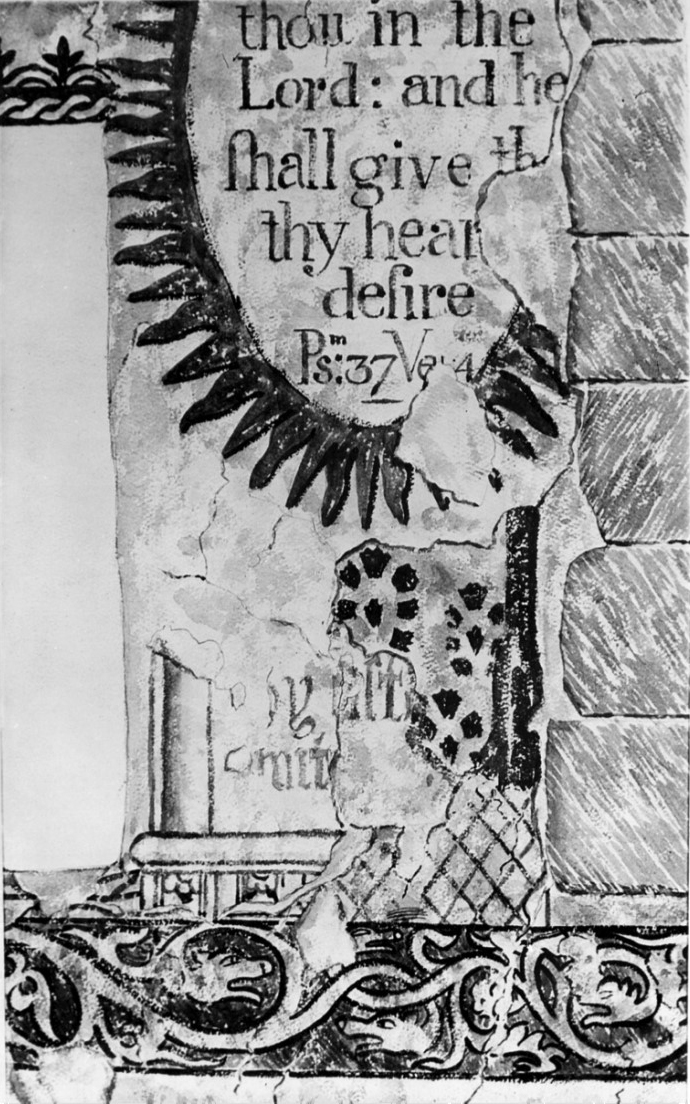

On entering the church by the south door the visitor will see the most complete of all the remarkable wall paintings, the Lord’s Prayer on the North wall. It is complete and readable. It belongs to the last series of wall paintings in the 18th Century. Stepping into the church the visitor will be surrounded by wall paintings and may feel that they have walked into a maze. The wall paintings date from the late 12th to the 18th century, each cycle painted on a new skin of lime. The last wall paintings, thought to have been painted in 1723, if the date on the ceiling in plaster relief is the guide, included the Lord’s Prayer, the Ten Commandments, the Apostles’ Creed and several Biblical texts. All the wall paintings are in the Nave, the main body of the church. There are no paintings in the Chancel.

Not all the paintings are religious. Above the Chancel Arch is the Hanoverian Coat of Arms, painted in a prominent place to show the village’s loyalty to the regime that replaced the Stuarts. At an earlier time and again as a show of loyalty, following the death of Queen Elizabeth, the last of the Tudors, an ornament was painted above the north door, and though now rather indistinct, it shows a decorated Thistle representing Scotland for James the Sixth of Scotland came to the English throne as James the First of England. Though removed when the wall paintings were uncovered in the 1950’s, above the South door there was a similar decoration, a Rose to represent England.

The earliest paintings, a series or cycle of paintings, tell the Life of St James the Great to whom the church is dedicated. The cycle of paintings were probably painted soon after the church was built, and most probably at the wishes of the Archer family who had asked for permission to build the church. The life of St James is told through a series of paintings beginning to the right of the chancel arch where the apostle receives the staff of Christ, the staff is the T-shaped ‘baccalus’ which pilgrims from at least the 11th century carried and had blessed before making their pilgrimage to Compostela in Northern Spain where St James, according to Medieval legend, was buried.. The story of St James then unfolds in a series of scenes stretching around the nave of the church before returning to the left of the chancel arch, where the last visible scene, following their execution, is of the heads of St James and of Josias shown on a napkin supported by the arm of an angel, symbolising their souls being carried up into heaven. Clive Rouse, who was responsible for uncovering and consolidating the wall paintings, believed there may have been up to forty scenes in the cycle of which he identified twenty eight, the others lost to the ravages of time.

A Blank Canvas

It is well to remember that Clive Rouse and his team had no idea of what treasure would be revealed when they began the task of uncovering the paintings. Their task would take four summers in the 1950’s to complete. It was the good fortune of the parish that the Victorians, who did so much to renovate churches throughout the land, did not remove plaster from the walls though they did strip the plaster from around the Norman windows. With no knowledge of what lay under each layer of lime wash Clive Rouse took the bold decision to reveal the earliest paintings, whatever they might be.

There was a ‘Eureka Moment’ when Clive Rouse announced to his fellow workers, “I know what this is! These paintings are about St James.” Perhaps the dedication of the church helped him to see the light. The task then became to uncover as much as was possible of all the scenes relating to the Cycle of St James and, thereby, sacrificing with much regret, some of the later paintings. The Lord’s Prayer was saved as there was nothing of the story of St James underneath. The same could not be said of the Ten Commandments, also on the North wall, and originally painted as two panels side by side, for all that remains now are the upper parts of the panels. The Apostles’ Creed on the South Wall was stripped of all but a few fragmentary words, here shown in red … who was conceived by the Holy Ghost, born of the Virgin Mary, suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, dead and buried … . The intention of Clive Rouse was to leave evidence that the Creed was there so that future generations would know.

Who was St James? The Biblical Evidence enhanced by Medieval Legend

Early in The Gospel of St Matthew, on the shore of the Sea of Galilee Jesus invited James, together with his brother John and two other fishermen, Simon and Andrew, to be his companions, the first of his disciples. Later, Jesus gave Simon the name Peter. After the death and crucifixion and resurrection of Jesus, James and Peter became leaders within the church. The preaching of the disciples to the Jewish community greatly added to their numbers. Their success did not go unnoticed, particularly by the Jewish leaders, and James was arrested and killed. His death is recorded in the first verses of the 12th chapter of the Acts of the Apostles:

“It was about this time that King Herod launched an attack on certain members of the church. He beheaded James, the brother of John, and when he saw that the Jews approved, proceed to arrest Peter also.”

The story of St James is told in the Acts of the Apostles but as told in the wall paintings it is embellished by the Medieval Legend of St James; the magician Hermogenes, Philetus and Josias have no place in the Bible. As the first of the Apostles to be martyred, St James was venerated, as were all martyrs, by a growing Christian population. From early times there were colourful accounts of the lives of all the apostles. Some of these were written down in the 5th century and ascribed to Abdias, first bishop of Babylon; written in Hebrew they were later translated into Greek and Latin. A Latin version was prepared in the 6th century by Julius Africanus, and is usually called the ‘pseudo-Abdias’, and this may have been the source for the story of St James as told in the wall paintings at Stoke Orchard.

Who was the artist?

A frequent question asked by visitors. The artist was probably a travelling artist but is unknown. It was the view of Clive Rouse that lectionaries, martyrologies and legendaries surviving from the 11th and 12th centuries often contained cycles of illustrations, and these illustrations may have been copied from the decoration of crypts or chapels. It is possible, he thought, that one of these illustrative books was used by a travelling artist in the decoration of the church at Stoke Orchard. No such book relating to James has ever been discovered.

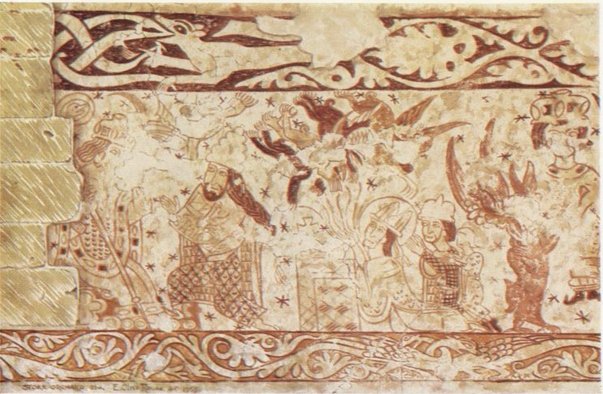

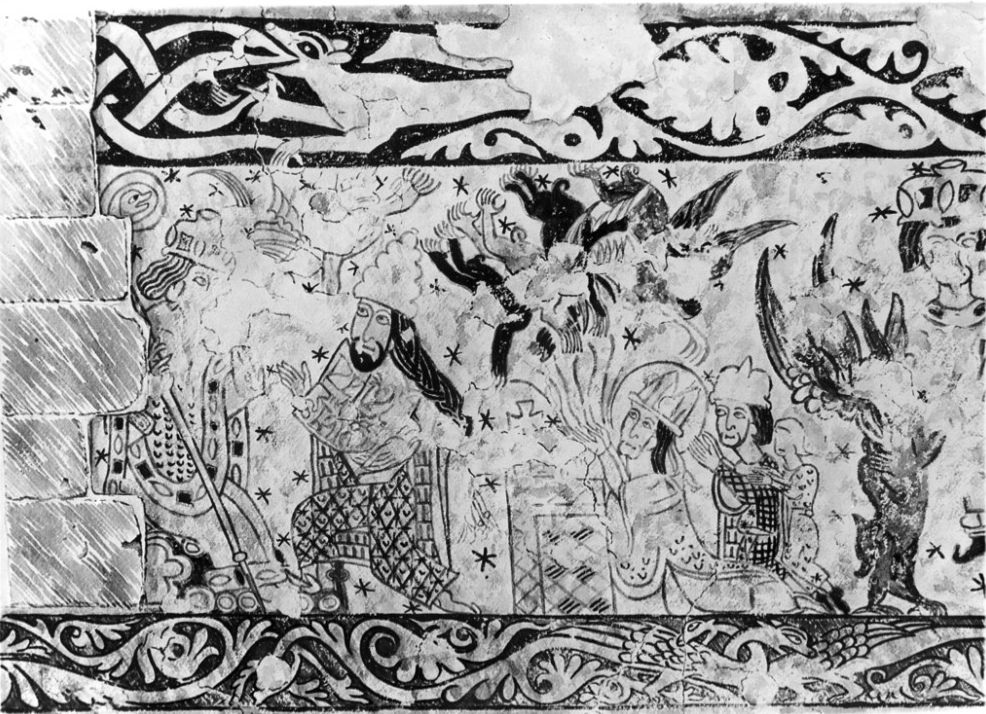

The story of St James as told at Stoke Orchard is contained within two borders, unique in England for their detail and variety and are worthy of attention. The two borders are quite different, the upper border is wider but in both the artist has painted serrated leaves, tendrils, scrollwork, knots and dragon-like creature Taken together, the story of James and its decorative borders, we see the church’s very own ‘Bayeux-style Tapestry’ – a 12th century ‘Cartoon strip’ telling the life of St James.

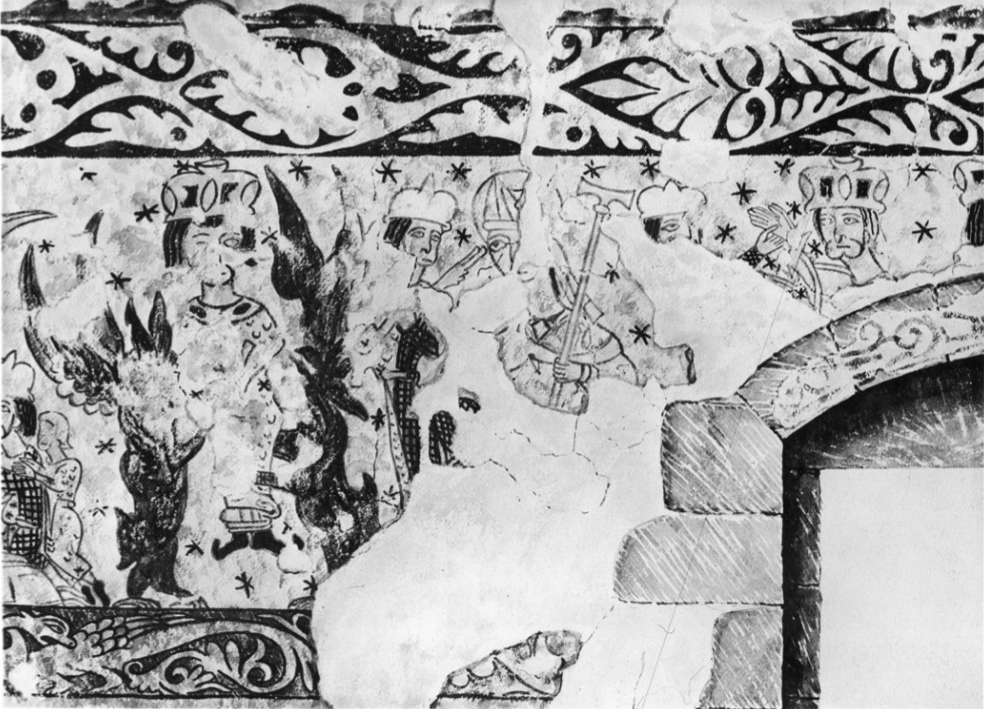

There is no marked division between the three scenes of the story shown above:

- The first scene has the seated figure of the magician, Hermogenes, and kneeling, pleading with him, is a bearded figure with hair in a long plait. He may be Abiathar, the High Priest of the Jewish Community, who, worried by the preaching of St James, begs Hermogenes to use his magic against James.

- Hermogenes sends devils, as shown as flying demons, to bring James, Philetus and his son to him but the devils are driven off by the prayers of the saint.

- Hermogenes, identified by his hat, is now shown bound hand and foot, raised from the ground by a winged devil on either side.

The National Coal Board Research Establishment

Before looking at the Story of St James as told in the wall paintings in detail, it should be acknowledged that the NCB Research team, and at the time sited in Stoke Orchard, having the experience of photography underground, became an essential part of the restoration team, photographing the wall paintings mainly at night “to avoid halation and oblique light from windows. Lighting was usually indirect and well diffused so as to avoid too much contrast. It was found in photography that plates with a special emulsion or very sensitive panchromatic film were best. Where detail on the wall was very faint, it was brought out by the use of filters and deliberate over-printing for that particular feature” (Clive Rouse p. 117). Remarkably, the photographs captured details that the naked eye cannot see. The information gathered by the NCBRE was used by Clive Rouse as he made measured drawings and paintings of the scenes of the Cycle.

Black and white copies of the sixteen paintings made by Clive Rouse are on display in the church. The original paintings are in the care of The Society of Antiquaries of London, Burlington House, Piccadilly, London W1J 0BE

The Story of St James as told in the Wall Paintings at Stoke Orchard: (Download the full PDF file here).

All the descriptions are taken from the “Wall Paintings in Stoke Orchard Church, Gloucestershire” by E Clive Rouse and Audrey Baker, and published by the Royal Archaeological Institute (May 1967)

1. Scene 1. (To the right of the Chancel Arch) Christ calling St. James and the giving of the staff.

Scene 1 Christ has long hair and a close beard; he wears a robe sprinkled with crescents. The figure on the right (St James) has his head bowed. Is he receiving a blessing? On a smaller scale to the left of Christ are two unknown figures. This scene appears in the glass of Chartes Cathedral, where the story of St. James is told in thirty panels, but told with differences reflecting their different sources.

In this scene there is part of the upper border.

The paintings at the east end of the south wall have been destroyed; destroyed by damage to the plaster and by the insertion of a late medieval window. Scenes may have shown James preaching in Judea, as at Chartes, and of Hermogenes, the magician, sending his disciple Philetus to confront James.

The people in the frieze lack proportion but are recognizable in quite fantastic clothing. James wears ecclesiastical vestments and always with a mitre on his head; the most elaborate clothing belongs to the magician Hermogenes and, to a lesser degree, Philetus, the hat of Hermogenes the larger and most elaborately jewelled.

South Wall: The scenes as far as the 16th Century window have been lost except for a small part of the lower border.

2. Fragments of early border and later paintings 15th, 16th, 17th, and 18th century.

In this photograph, on the end of tendrils, and part of the lower border, are three small animal heads with open mouths.

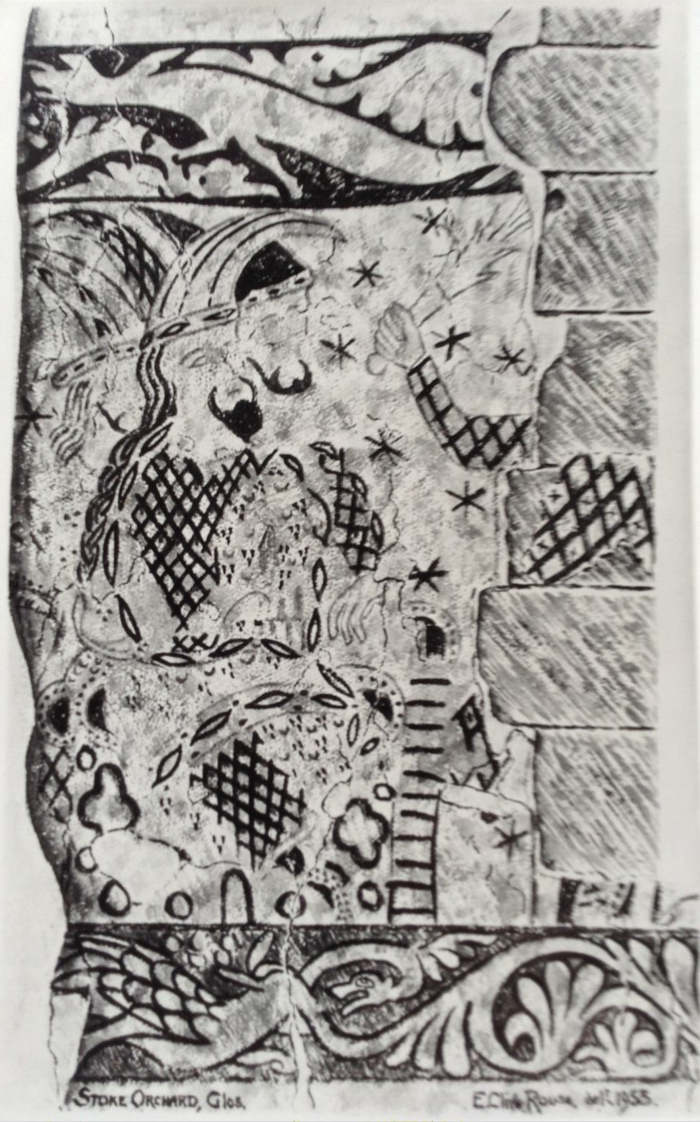

3. Scene 2. (left splay) Philetus disputing with Hermogenes the Enchanter.

Scene 3. (right splay) Philetus thrown into a tower, with chains.

Here, the plaster has been stripped back to expose the stonework. In scene 2 on the left, just the feet and lower legs of Philetus remain. Hermogenes, the magician, is arguing with Philetus, once his disciple. Hermogenes is wearing an elaborate jewelled head-dress and a multi-patterned robe.

In scene 3, on the right splay a figure, a guard perhaps, is blowing a horn.

Behind battlemented walls a semi-prostrate figure is seen, chained by the neck with his hands bound.

4. Scene 4. The chief Pharisee seeks the help of Hermogenes to destroy St. James.

Scene 5. St. James, at prayer beset with devils, protects Philetus and his son.

(Scene 6)

In scene 4, the seated figure, Hermogenes, is seen wearing a cape-like garment decorated with lines of crescents and having a jewelled border; he holds a long staff with a grotesque head. Pleading with him is a bearded figure with hair in a long plait; he may be Abiathar, the High Priest, who, worried by the preaching of James among the Jews of Jerusalem, wishes to smear the reputation of the apostle, and begs Hermogenes to use his magic against James.

Note the trellis-patterned trousers with crescents in the lozenges. At Chartes cathedral in France, the story does not show the priest.

Hermogenes decided to send his disciple Philetus to confront James and to discredit the faith of the apostle but, after listening to James, Philetus was converted. He returned to Hermogenes, claiming that the doctrine of James to be true and recited to him the miracles he had seen. He counselled Hermogenes to become a disciple too. In anger, Hermogenes incarcerated Philetus with magic bonds as a punishment, but Philetus sent his servant or son to meet James asking for his help to free him. James gave him his sudarium (a kerchief or napkin with miraculous powers). The servant returned and laid the sudarium upon the bound Philetus who was instantly freed from all the enchantments of Hermogenes.

In scene 5, the enraged Hermogenes sends devils, shown as flying demons with wings and claws, to bring James, Philetus and his son bound before him, but they too fell under the Saint’s power.

In the larger border a scroll spews from the dragon’s mouth. With human hands the dragon is beautifully drawn, but is the dragon a power for good or evil? Below to the left, a bird-like head appears, and, to the right, two entwined dragons appear to be biting their own backs.

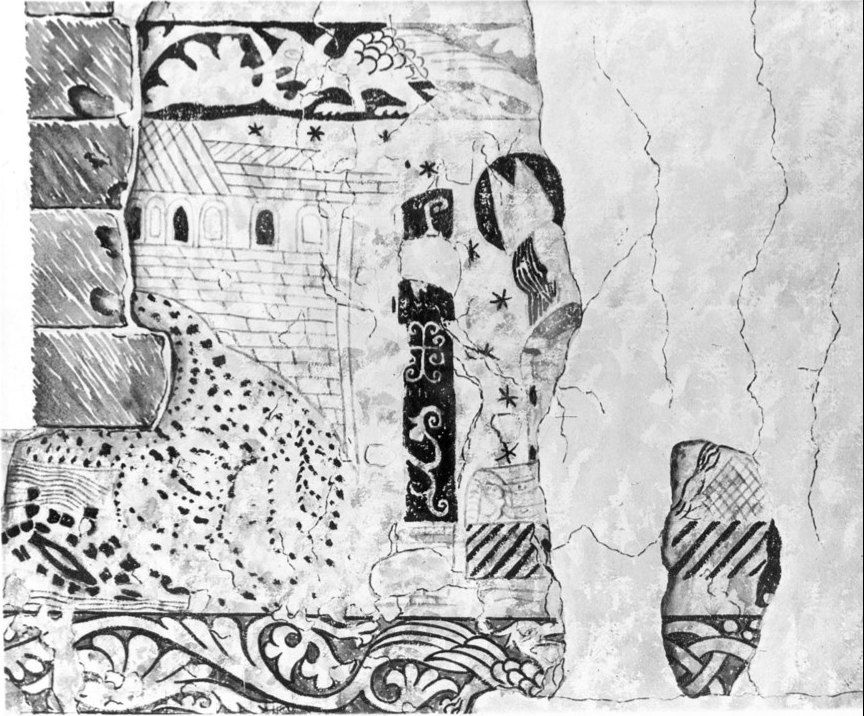

5. Scene 6. Hermogenes seized by devils at the command of St. James.

Scene 7. St James (holding staff) tells Philetus to unbind Hermogenes.

Scene 8. Philetus unlooses Hermogenes’ hands.

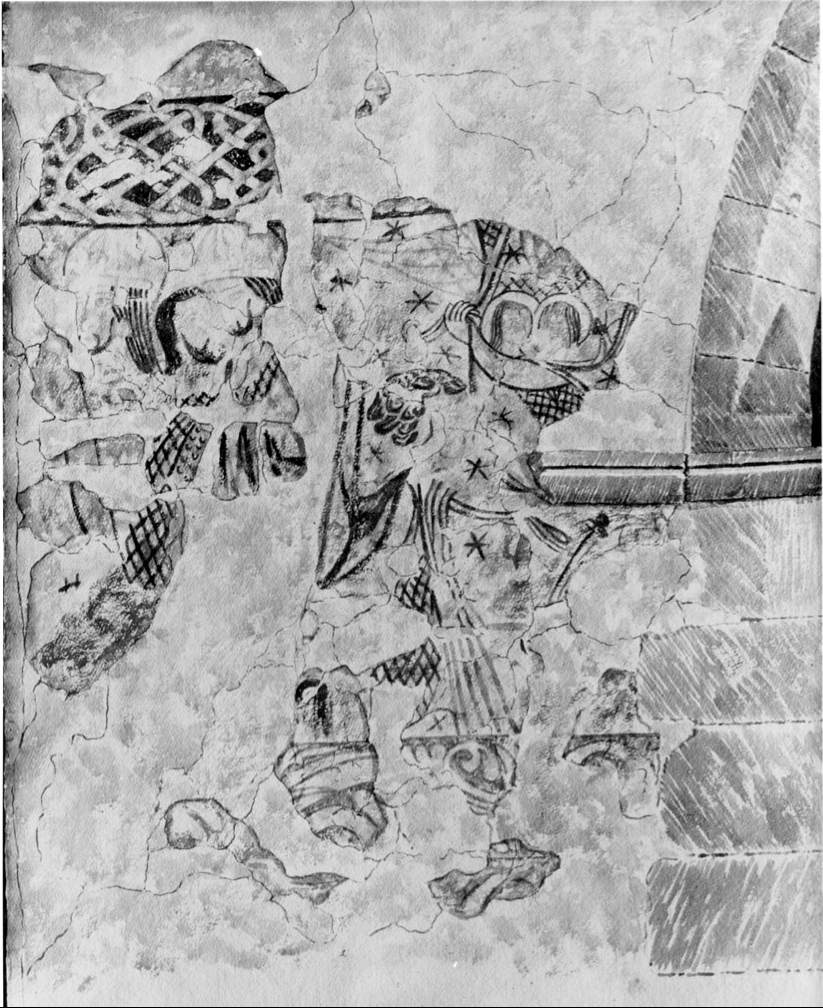

In scene 6, Hermogenes, identified by his hat, is shown full face and is bound hand and foot. He is raised from the ground by winged devils on either side. The curved form of his shoes with up-turned toes stresses his connection with the occult. James, having loosed the demons, sent them to bring Hermogenes before him, bound but unharmed.

In scene 7, there are breaks in the plaster, but it is possible to identify two figures in the centre; that on the right is clearly James, for a wears a mitre. With a tau-headed staff in his left hand he talks to Philetus, who is identified by his hat and chequered garments.

In scene 8, a nervous Philetus does as asked by James and reaches out to untie the wrists of Hermogenes. Hermogenes is converted. Over the east end of the south doorway only the head and a hand of Hermogenes has survived.

In the bottom left corner we see the dragon biting its own back.

The background, here and elsewhere, is dotted with crude stars, and are part of the 12thcentury decoration.

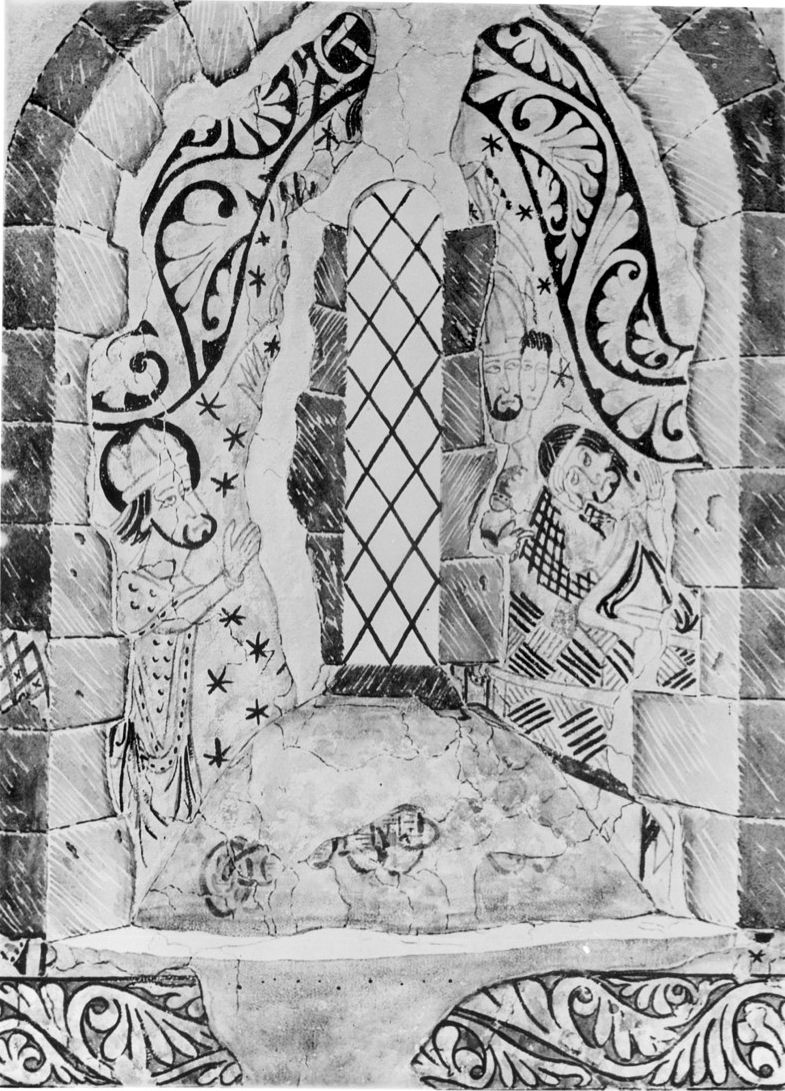

6. Scene 9. (over south door) Hermogenes and St. James converse.

Scene 10. (over south door) Philetus’ son tells his father to fetch St. James’s staff.

Scene 11. Philetus hands the staff of St. James to Hermogenes.

In Scene 9, the heads of Hermogenes and James, identifying them by their hats, are visible. More clearly seen in the stained glass of Chartres Cathedral, Hermogenes is overcome and ‘all confused’ by the generosity of St. James.

In scene 10, are the heads and shoulders of two figures: to the left is the son of Philetus, who is small and hatless, raises his hand as he converses with his father.

In scene 11, Philetus, still half-length, has the tau-headed staff of James in his right hand while pointing to it with his left. Hermogenes, on the right, reaches out to receive it. Fearing attack from devils, Hermogenes had asked for something which belonged of James, by which he may be protected.

Hermogenes still wears his identifying hat but he has abandoned his vestments and magician’s shoes in favour of a simpler cloak and simple shoes that come up round his ankles.

7. Scene 12. (left splay) Hermogenes hands his books of magic to St. James.

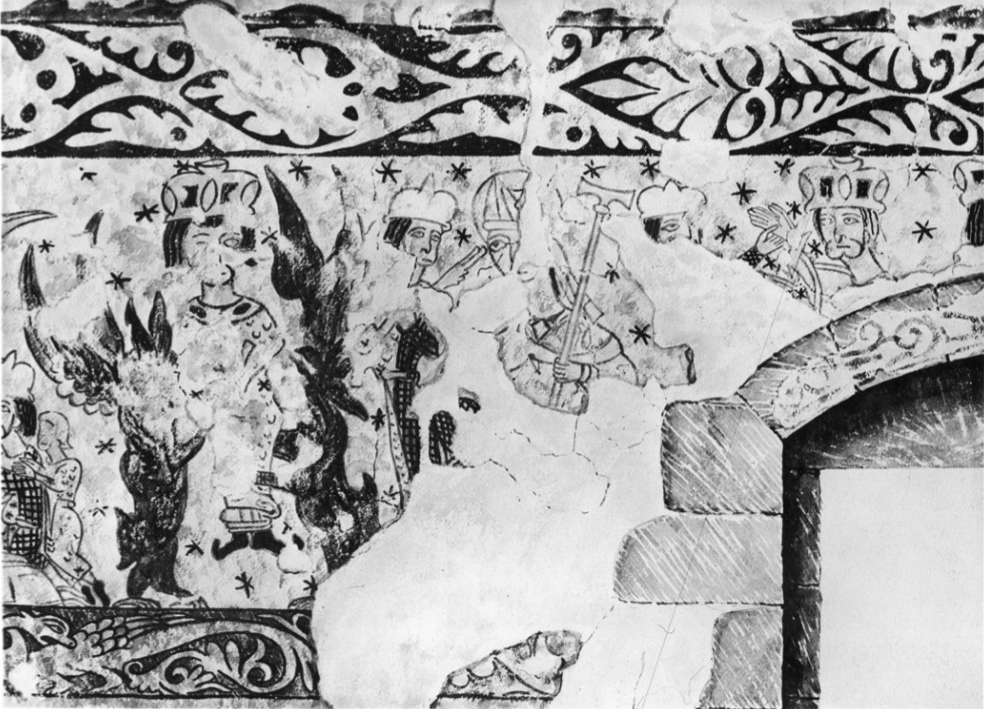

Scene 13. (right splay) ? The shrine in which the evil books were kept.

In scene 12, with hat slipping off, the head of Hermogenes is shown by the window; facing him are the hinges and ties of a book. Hermogenes gives his books of magic to James.

In scene 13, on the right splay, what looks like a building, is possibly a reliquary or ‘Zaberna’ in which Hermogenes kept his books. The Zaberna is not shown in the glass of Chartres.

On the sill, cloth and shoes of a figure, possibly of Hermogenes.

8. Scene 14. Unidentified. ? A Familiar of Hermogenes in argument.

Scene 15. St. James, Hermogenes and a sailor cast the evil books into the sea.

Scene 16. Unidentified ? Another Familiar of the former Enchanter.

In Scene 15, the books of magic are thrown into the sea (rather than being burnt and fouling the air), the scene coming between two figures, both shown with patterned clothing. On the left (scene 14), we see a figure in profile, who has curling and interlacing locks of hair, and who faces another of which little remains. At the bottom of the stripped window jamb are the feet of this unknown character, and at the window’s edge, the jewelled border of a robe. A hand reaches out to the figure.

To the right of the boat scene, scene 16, a second fantastic figure, similar to the figure in scene 14, is apparently addressing a figure opposite to him of which little remains. Who are these mysterious figures in patterned cloaks? Are they evil-doers or familiar spirits, former associates of Hermogenes?

The boat has thick masts fore and aft. Hermogenes, with his hat, is in the middle, James in his mitre to the left and a hatless figure, probably a boatman, to the right. Books, shown as rectangular objects, are falling into the water; below these are rough vertical lines, which might represent tongues of flame.

West Wall:

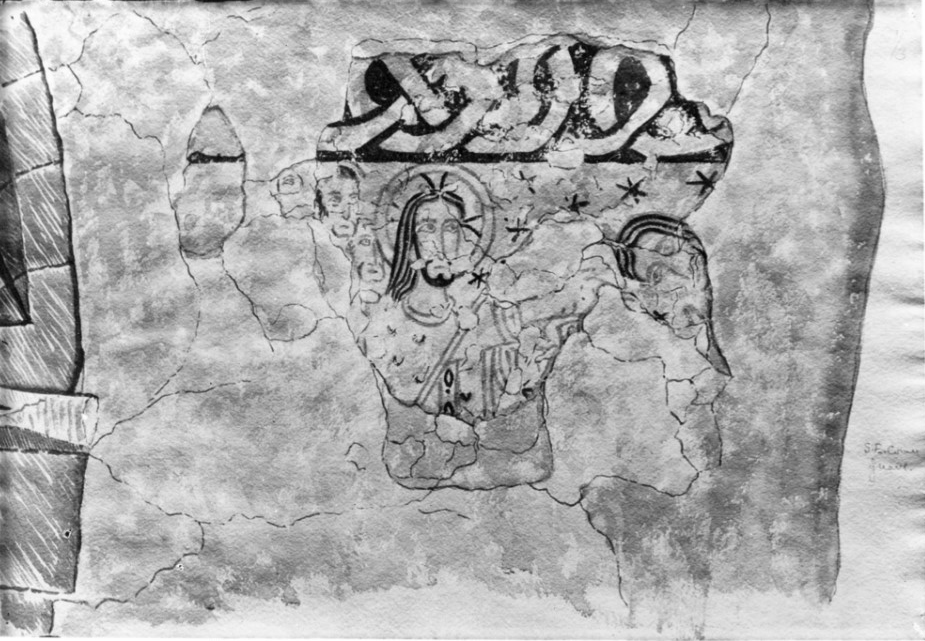

9. Scene 17. Uncertain. St James with staff overcoming Jews and Infidels by his preaching.

The Familiar is overcome by St. James.

Scene 18. A vision of Christ, in an attitude of blessing, assisting St. James.

The left half of the scene 17 has been destroyed owing to a settlement in the south-west corner of the building. There are two figures to the left of James, the smaller with snaky locks and chequered garments, the other in a long tightly fitting garment: though idols were usually shown unclothed, the one appearing to be kneeling may be an idol. At Chartres, Hermogenes is seen destroying a naked figure standing on an altar.

In the text of pseudo-Abdias, the probable source of the wall paintings at Stoke Orchard, when the repentant Hermogenes asked James for baptism James first instructed him to go from house to house telling all those who had listened to him that they had been deluded.

In scene 18, on the right, Christ, with his arms crossed in front of his body, is making a gesture of blessing. Is it possible that the wavy lines above the border represent water in which a recumbent figure is receiving baptism? Not only is there the celebration of the sacrament of baptism, but also a celebration of the Christ’s triumph, of Christ over the powers of evil as symbolized by the dragon.

In the upper border two discerning faces look on.

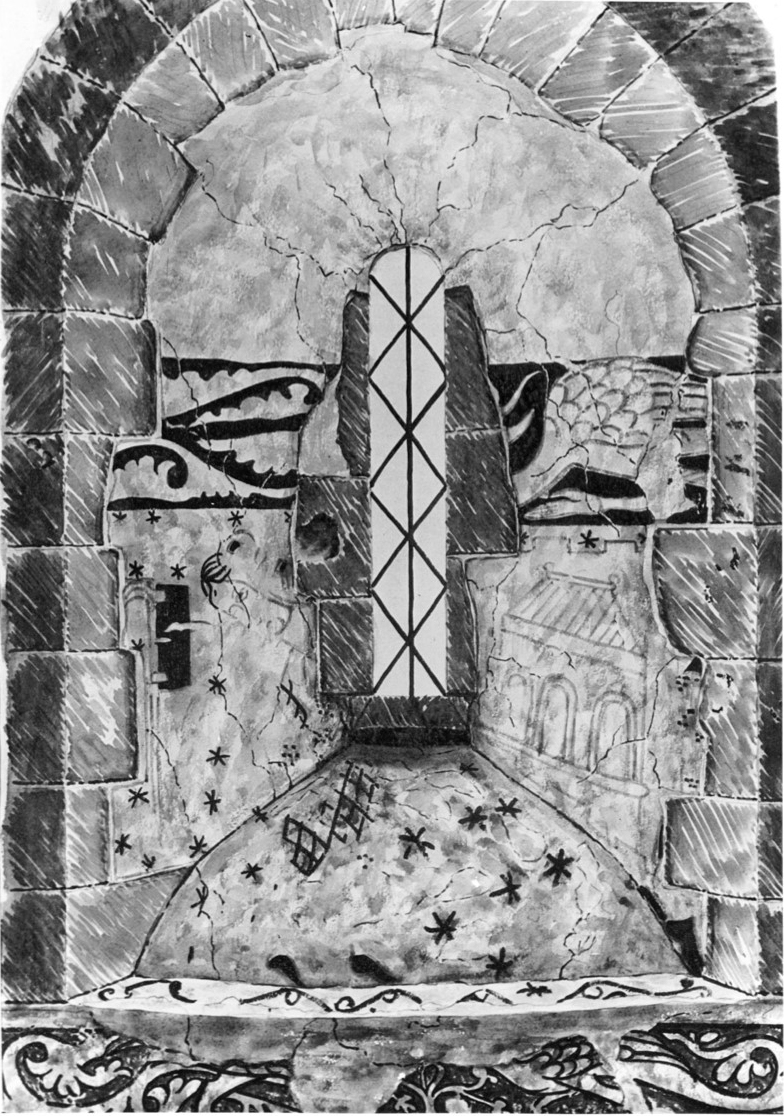

10. Scene 19. (left splay) St James baptising converts.

Scene 20. (right splay) Unidentified. A dragon on the sill is part of the scene.

In scene 19, the mitred James raises both hands and holds them above the small uncovered heads of two standing figures, who are perhaps immersed in water as the wavy lines below them suggest. Behind James are the bare heads of three bearded figures; are they also waiting to be baptised?

Along the bottom of the sill there are more wavy lines with some creature representing the powers of evil from which the baptised have been released.

In scene 20, to the right of the figure with beard and dark hair the spotted and blotched area may represent a scalloped wing of a dragon or monster.

11. Scene 21. Probably a continuation of the last: St. James preaching before the prison doors.

The upper border shows a winged and clawed dragon with long ears and who holds the stems of a scroll in his mouth.

Scene 21 Another blotched and spotty area suggests the second wing of the dragon, while, above it is part of a building with masonry walls, a gabled roof, and a series of windows, three of which seem to be blind. To the right a figure with a very high pointed mitre, suggesting James, is kneeling on a kind of platform, indicated by heavy diagonal lines.

It seems probable that the scene corresponds with the story at Chartres, where the saint, having been thrown into prison, delivers a sermon to his disciples from his cell.

There is a break from the north-west corner to just east of the north door where the wall has been rebuilt or refaced, accounting for a number of scenes to the identity of which there is no clue. Eight scenes may have been lost at this point. The story at Stoke Orchard continues with the scourging and death of St. James, where, in part at least, the story is Biblical; in a brief line of the twelfth chapter of the Acts of the Apostles we read……… “It was about this time that King Herod attacked certain members of the church. He beheaded St. James, the brother of John, and then, when he saw that the Jews approved, proceeded to arrest Peter also.”

North Wall:

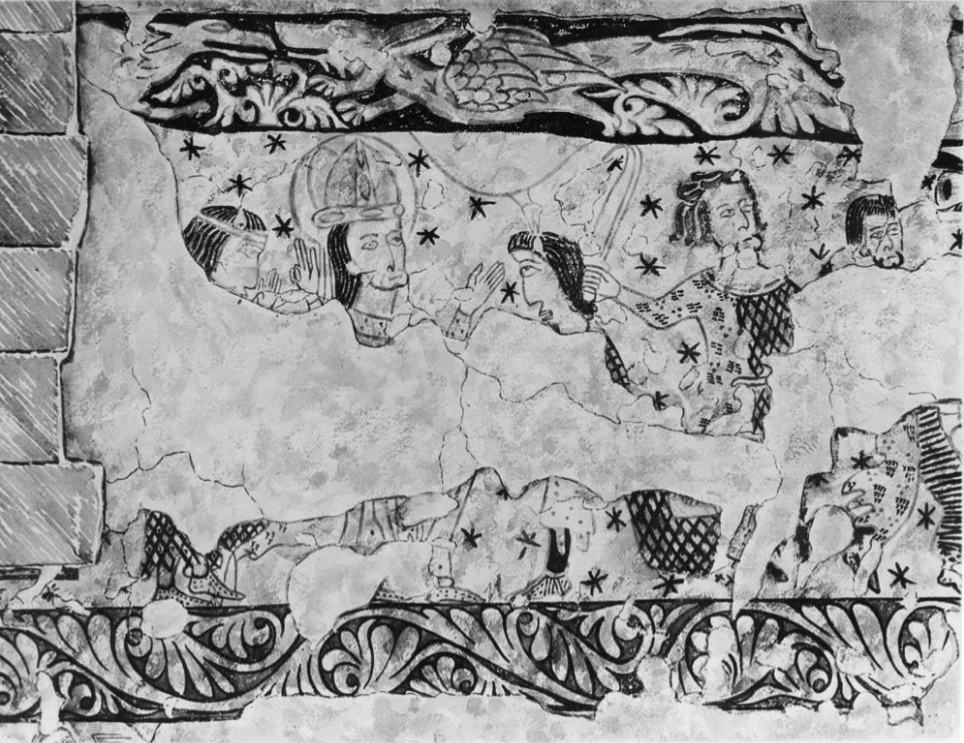

12. Scene 22. St James scourged and condemned before Herod Agrippa and his court.

Scene 22 In the centre is a figure wearing an elaborate head-dress and robes seated on a throne. He has a long beard and his hair falls over his shoulder; his cloak, highly patterned, has a heavily jewelled border. Over his left shoulder is an attendant. The centre figure may represent King Herod or Abiathar, the High Priest.

Owing to the stripping of the plaster only the upraised arm with a scourge grasped in the hand of the torturer and fragments of the trellis-work tunic survive. In the window splay (scene22) kneels James wearing mitre and vestments.

(A clue that this is a photograph of a painting is seen in the dedication at the bottom of the scene.)

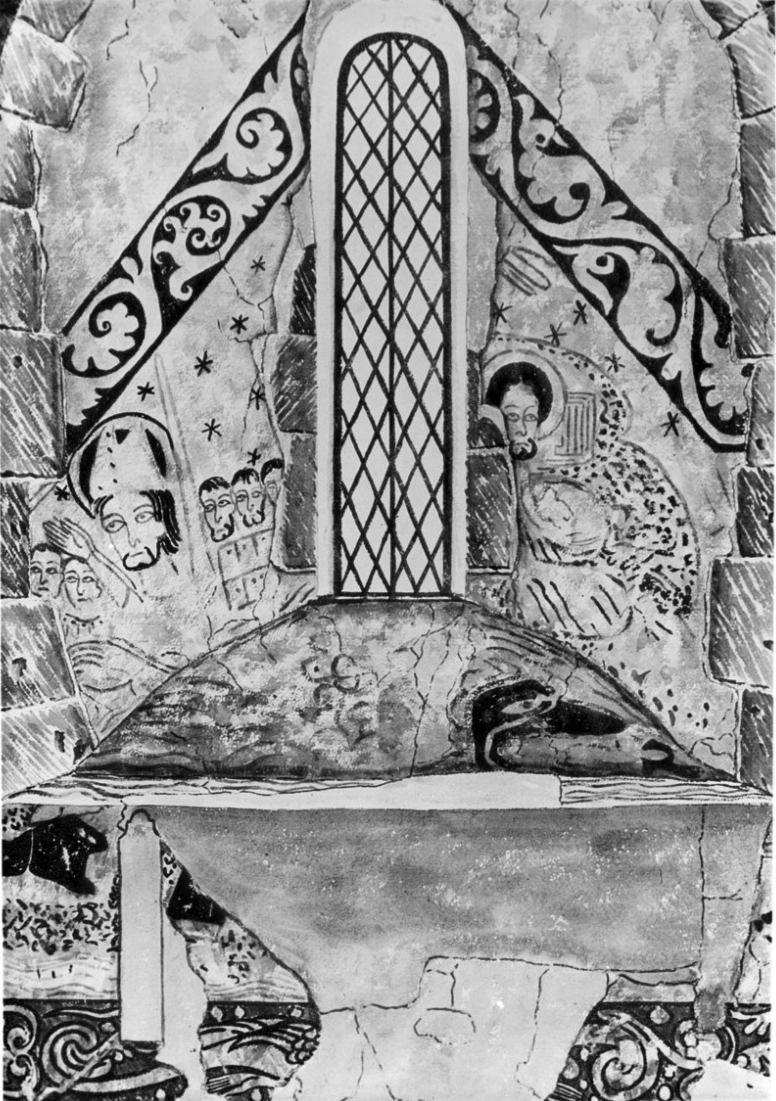

13. Scene 22 continued (left splay) St James between his tormentors.

Scene 23 (right splay) St James led to execution heals the paralytic.

Josias looks over his shoulder.

In scene 22, a second scourge is just seen to the right of the head of James.

In scene 23, the mitred head of the saint with a hatless figure close beside him approaches a figure in the foreground that seems to be lying on a chequered pavement with his head supported on a cushion with a trellis-patterned cover. He raises a hand as if appealing to the saint and, with the other, touches a bandage which is bound round his head. This incident is shown at Chartres where a cord about the neck of James is visible.

In the texts, this incident took place while James was being led to execution by a scribe called Josias.

14. Scene 24 St. James, blessing the healed man and Josias is converted, whose head a dove touches.

Scene 24 In the centre, James wears a mitre different in shape from that worn in other scenes. He raises both hands and gives his blessing with his right.

To the left of James is the head of the paralytic, identified by the bandage, who raises a hand in adoration. To the right is Josias who kneels on one knee. Both the paralytic and Josias are shown in profile and wear trellis-patterned garments and decorated shoes. A dove emerges from a cloud above and touches the head of Josias.

In the texts it is recounted that Josias, so amazed at the healing of the paralytic, was converted and, kneeling down, begged for absolution and baptism. At Chartres, both the paralytic and Josias are shown kneeling before James.

In the upper border, two creatures with feathered wings face one another; their heads are long and large with big ears, while their tails are thick. The plant between them is elaborately scrolled.

15. Scene 25. Josias is assaulted and his ear is cut off in the presence of Abiathar, the High Priest.

Scene 25 On the left, partly overlapping the figure of Josias in the last scene is a spirited figure brandishing a sword or scimitar in his upraised right hand. He has snaky locks, associated with evil doers, and represents the executioner. Half of his tunic is patterned with groups of dots while the other has trellis design. His left hand seizes the neck of a figure before him, who probably represents Josias.

Josias has short straight hair; one leg of his trousers is decorated with the same material as the executioners, the other decorated with horizontal bands. Both his feet are slightly off the ground.

Facing Josias, to the right, is a commanding figure seated on an architectural throne. His horned head-dress is perhaps the most fantastic shown in the whole series of paintings; it is like a Byzantine crown. His straight hair is worn hanging to the shoulder. The cloak is fastened at the neck. Drapery of a lighter material falls in front of the right part of the throne.

Texts tells us that the High Priest demanded that Josias should renounce his Christianity and, when he refused, commanded that he should be… ‘struck on the mouth with fists’, and then sent to Herod with the request that he should be executed with James. At Chartres, in the presence of a lady, the ear of Josias is cut off and red blood streams from the wound.

In the upper border we see the long broad tail of the creature from the previous scene.

To the left of the Chancel Arch:

16. Scene 26. (continues from the north wall) St James asks for water to baptise Josias.

Scene 27. St. James embraces Josias.

Scene 28. The execution: and the souls of St. James and Josias carried up to heaven in a napkin

Little of the scene 26 on the far left remains. The head of James with his mitre alone is clear. This scene probably shows the baptism of Josias before his martyrdom. All texts describe how, when Josias begged for baptism, James asked the executioner for ‘a pot of water’ and with this he carried out the sacrament. The scene is not shown at Chartres.

In scene 27 are two figures, Josias and James, embracing.

Lastly, in scene 28, amongst the confusion, above the block of the chancel pillar, there are two heads with haloes on a napkin, which, supported by the arm of an angel (whose wing appears just below the upper border) shows the souls of James and Josias being carried up into Heaven.

Is that the End of The Story? Comparison with the French Cathedrals

The last scene of The Story of St James, depicted in the Rose Window at Chartres, is Christ in Glory. Might we assume that a similar scene (in place of the Hanoverian Arms) completed the story of St. James at Stoke Orchard before the chancel arch was partially rebuilt in the 14th century. There are other isolated examples at other French cathedrals showing the Story of St James, as well as a variety of texts, but while showing the story slightly differently they give authenticity to the story so described in the unique wall paintings at Stoke Orchard. What can be learned from these other sources is that the final scene as shown at Stoke Orchard may not have been the souls of St James and Josias being received into heaven.

A National Treasure

It never ceases to amaze that this little remote medieval church should have been painted with this wonderful cycle of St. James, Apostle and Martyr. How wonderful the walls must have been when first painted; if only we could turn the clock back. Other churches in Northern Europe may have been similarly endowed, but now this church stands unique; it is no exaggeration to say that it is a Village, Parish and National treasure. We struggle to understand why this little church in remote Medieval England should be so fortunate. It is easy to imagine that it may be the gift of an unknown wealthy patron, or by a member of the Archer Family, Lords of the Manor. If it was the Lord of the Manor we have to ask why. Was he seeking to impress his landlords, King Henry II (1133-1189), and the king’s cousin, Earl of Gloucester, William Fitz Robert? Henry and William were cousins, sharing the same grandfather, Henry the 1st who had founded the Cluniac Abbey at Reading, enriching it with the relic of a hand of St James given to his daughter Empress Matilda when visiting the shrine at Compostela. Following the 20 years of civil war (1135-1154) after the death of Henry the 1st one of the principal religious programmes of Henry the 2nd was the restoration of the status of Reading Abbey, guardian of one of the principal relics of James the Great outside Compostela. The second landlord, the Earl of Gloucester, was also strongly linked to the Jacobean cult as his own father (an illegitimate son of Henry 1st.) was the patron of the Priory of St James in Bristol.

St James of Compostela

The Legend of St James did not end with his martyrdom. It was further elaborated by an account of how the body of James was smuggled away by two of the disciples of James (Hermogenes and Philetus in some versions) who laid it in a rudderless boat which was at length washed up on the shores of Galicia (north-west Spain), the territory of the heathen Queen Lupa. She allowed the disciples to bury the body of the saint. The spot where he was buried was lost until, around the year 815, a Spanish hermit had a vision in which he saw a bright light shining over a spot in a forest. The matter was investigated and a tomb of the Roman-era containing St. James’ body was found. The bishop of a nearby town had a church built on the site. Around this shrine the city of Santiago de Compostela grew and began to attract pilgrims, who steadily increased in number until by the eleventh and twelfth centuries, a half-million pilgrims a year were making their way to Santiago. Now, even after more than a thousand years, the shrine at Compostela continues to draw Christians from around the world.

Santiago da Compostela

Venerated as the oldest apostle, the first to suffer martyrdom and thus the first to enter heaven, the shrine at Compostela drew pilgrims, many believing that the saint had special power over evil spirits and disease. The pilgrimage to Compostela was popular in England.

Very few churches and religious houses in England were dedicated to St. James prior to the C12th, but by the middle of the C14th churches, religious houses and Hospitals named after the saint totalled 355. The proliferations in the C12th occurred around the time when Compostela was elevated to an Apostolic See, thus raising the saint’s profile. News about the cathedral, which then was immersed in an intense building programme, would have reached England by travellers, pilgrims and itinerate artists, such as masons and artists. Pilgrimage to Compostela suddenly became fashionable though pilgrims began arriving in Compostela in the C9th. The churches dedicated to St James are widespread throughout England. Although most pilgrims reached Compostela from ports on the south coast of England (Dover, Portsmouth, Southampton, Poole and Plymouth), pilgrims visiting Stoke Orchard would most probably leave from the port of Bristol. Pilgrims used an established road network connecting the principal urban centre with harbours. Churches and Hospitals dedicated to St James and meeting the needs of pilgrims were established near existing roads giving the pilgrim a safe route on their journey to Compostela. Pilgrims would have chosen the most convenient routes and ports to travel to the European mainland. The Cluniac Order promoted pilgrimages in England which meant that few pilgrims travelled alone. A whole network of Hospitals run by monastic communities provided much needed hospitality. Pilgrims had protection against arbitrary arrest and were exempt from tolls and taxes. (Marta Ameijeiras Barros: Mapping the Cult of St James the Great in England)

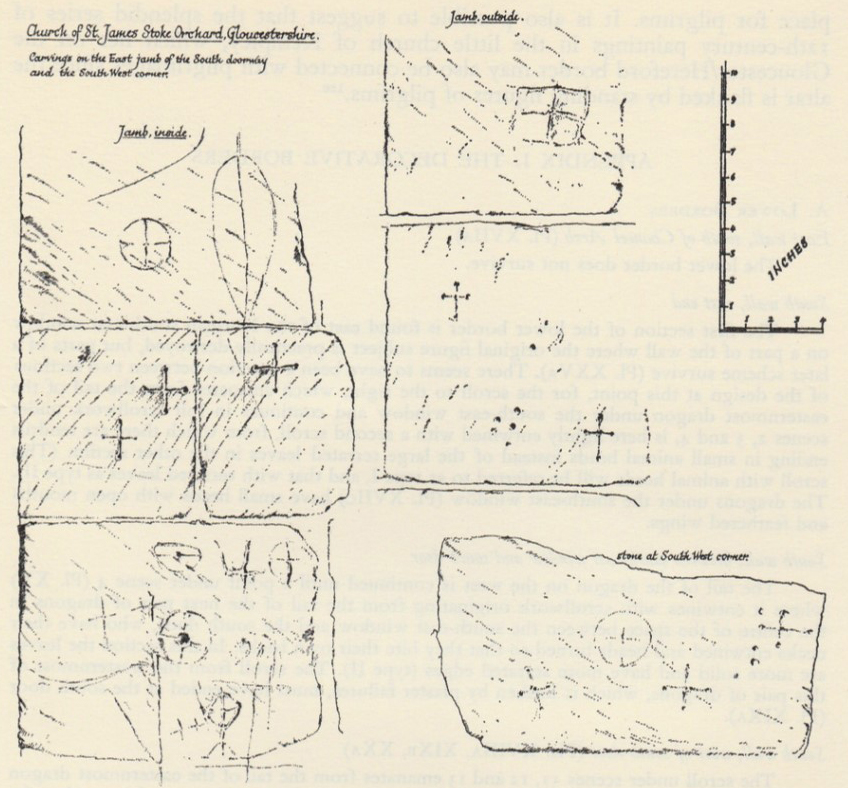

Stoke Orchard: a Halting Place for Pilgrims

Constance Storrs (Jacobean pilgrims from England to St James of Compostela: from the early twelfth century to the late fifteenth century, London, 1994 p.162) shows that in 1314 William Archer, tenant of the manor at Stoke Orchard, may have visited the Jacobean capital; but did he visit as a pilgrim? It seems likely that Stoke Orchard, around 50 miles from the harbour of Bristol, became a ‘Halting Place’ for pilgrims travelling from Wales and the north of England to the burial site of St James at Compostela. We can imagine that the church, though at times a place of quiet, would have been quite different with the noisy throng of its ancient visitors. The scallop shell became the symbol of St James and of all pilgrims (pilgrims attached the shell on their hats as a badge of honour) and fittingly the wooden offertory plate of the church is in the shape of a scallop shell. Occasionally, today’s visitors to the church not only sign their names but may also say that they have been to the shrine at Compostela. Visitors in the past have done more than that, in that they have left small incised crosses in the jambs of the south doorway and at the north door, the south west corner and on the reused stone at the south east corner. Those fortunate enough to visit the church may wish to look for the crosses, and while by the North door view the unusual hinges with their dragon-like appearance.

Dating the wall paintings (Clive Rouse)

1. There are no fewer than five successive schemes of painting in the church. (Five is a conservative estimate.) The first representing the Life of St. James is dated between 1190 -1220.

2. An extensive 15th century scheme included BROCADE PATTERNS IN RED and a large St. CHRISTOPHER on the South wall whose large unshod feet and ankles remain (seen below the lower border of the earlier cycle and above the numbered pews). One can only imagine the full painting; it would have dominated the wall. Pilgrims on the way to the Tomb of St James in Compostela, on entering by the North doorway, would have been cheered to see the patron saint of pilgrims. Fortunately, the painting of St Christopher was not entirely obliterated by Clive Rouse. A giant of a man he would have dominated the wall.

3. In or around 1547 (at the Reformation) all the earlier paintings were obliterated and replaced by texts in BLACKLETTER SCRIPT in frames.

4. In or around 1603 there was another redecoration when JACOBEAN ORNAMENTS were placed around the windows, a CROWNED ROSE and CROWNED THISTLE with the initials I.R. (Jacobus Rex) above the south and north doors, and the FIGURES OF TIME AND DEATH.

5. Finally in 1723 when the nave was renewed (the date of 1723 in plaster relief is seen in the ceiling) a further comprehensive series of TEXTS IN FRAMES and the HANOVERIAN ROYAL ARMS (over the chancel arch) were executed. Of this series five complete texts survive, with parts of three others, and the remains of the Royal Arms. Included in the last decoration, in an oval frame to the right of the south east window, a text from PSALM 37 “Delight thou in the Lord, and he shall give thee thy heart’s desire”. Also a text from the ACTS OF THE APOSTLES, almost unreadable, by the north door: “See here is water, what doth hinder me to be baptized?” Flanking the chancel arch are texts from THE REVELATION OF St JOHN and St JOHN’S GOSPEL.

Part of the Jacobean re-decoration, and crudely painted, on the West wall is DEATH AS AN ANIMATED FIGURE.

Hard to date

Above the upper border in the centre of the south wall is a scene that may depict DEVILS PULLING A HANDCART with faint traces of figures in the cart; the scene is probably a warning of the Torments of the damned in Hell. The much later painting on the West Wall showing a skeleton, its message much the same. Clive Rouse found it difficult to see how the devils and the handcart fitted into the various schemes. It is pre-Reformation. Though highly unlikely to have been painted at the same time as the Cycle of St James, it is painted on the same skin of lime wash as that of the Cycle of St James but unlikely to be as old.

The unanswered question: Why are there no traces of wall paintings in the Chancel?

This was a puzzle for Clive Rouse, but two discoveries may lead to the answer:

The Archaeological Dig of 1977

When the east end of the Chancel was in danger of collapsing in the 1970’s, and before it was underpinned, the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society carried out an archaeological dig under the direction of the field Officer Roger Leech in November 1977. It soon revealed that the chancel had been rebuilt twice. Probably at the same time as the chancel arch was rebuilt (13/14th century) the east wall of the chancel was shortened by about three feet. The reason for the rebuild is unknown.

The Recent investigation of parish records held in Gloucester Archives

Again, and for a reason unknown, the chancel was rebuilt for the second time, extending the chancel to its original length. When that happened is still unknown but a recent investigation of Parish Records has shown that money was still being raised in 1844 for “repairs to the Chapel in 1840 to 1842”. Later than this date a Non-Conformist chapel was built in the parish. The reference has to be to the church of St James, which as a Chapel of Ease to St Michael’s in Bishop’s Cleeve was probably always spoken of as being the Chapel with its Chapel yard. Can it be assumed that the repairs refer to the re-build and extension of the Chancel?

“What did the Victorians do for us?” With hand on heart, we can say that they rebuilt the Chancel at the beginning of the era, wisely reusing the 14thcentury stone and windows, re-plastering the whole of the Chancel and, as a final step, giving the whole church a new coat of lime wash. Any evidence of the 18thcentury decoration in the Chancel and in the Nave was lost.

In 2021 the walls of the church were cleaned and the wall paintings conserved by Mark Perry and Richard Lithgow. Their wonderful work was well-supported by many generous donations.

This little church gives us glimpses into forgotten worlds

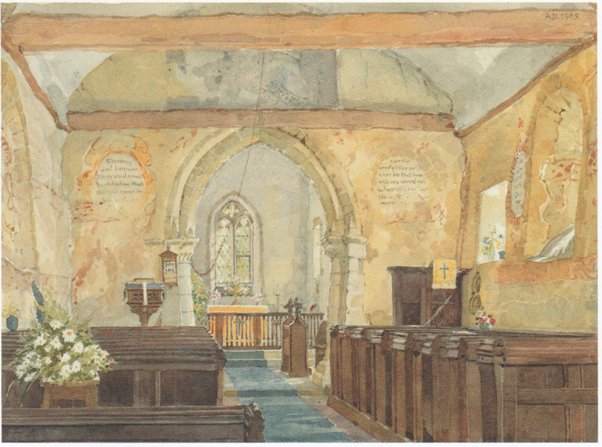

The interior of the Church of St James the Great painted by Arthur Bell R.W.A. (1897-1995)

Could it be that the Victorian ancestors ran out of money? The church did not suffer the fate of the sister church in Tredington where all the walls were stripped bare. What we have in the little church dedicated to St James, this little gem, are glimpses into forgotten worlds. Though historic, the church is not a museum but remains a place of worship for the people of the parish, and while enjoying the richness of this church’s heritage may all visitors find it a place of peace and prayer.

For those who like a challenge may wish to walk through quiet countryside on a circular walk, newly inspired and devised by Guy Vowles and the late Roger Grimshaw; called “A Pilgrimage Walk” from Tewkesbury Abbey. The triangular route, with countryside walks, goes to Stoke Orchard (8km) and to Deerhurst and Odda’s Chapel (both Saxon) (7.2km), along the River Severn and back to the Abbey (4km). Copies of the walk are in the church.

Acknowledgements

Thanks are due to the Royal Archaeological Institute for the reproduction of the painting by Clive Rouse and for the extensive use of photographs and notes from “Wall Paintings in Stoke Orchard Church, Gloucestershire” by E Clive Rouse and Audrey Baker, published by the Royal Archaeological Institute (May 1967).

For more details of the archaeological dig in 1977 - see ‘Excavation at Stoke Orchard Church’ (Transactions for 1983) pages 181-3 of volume 101 on the website of the Bristol and Gloucestershire Archaeological Society.

The painting of the interior of the Church of St James Stoke Orchard by Arthur Bell R.W.A is reproduced with the kind permission of David Boswell on behalf of Margaret Bell.

Rev. Chris Harrison 2025